Through Words and Lenses: Because Apparently, Reading Makes You a Better Photographer

We all know reading can whisk us away to new worlds or even provide a cozy refuge on a rainy day. However, its influence is often overlooked in photography, primarily documentary work. Even so, diving into photography theory has recently underscored just how transformative reading can be. For a documentary photographer, it's like sharpening an unseen lens that hones our ability to observe, connect, and capture life as it is.

There are countless books on photography, each teaching something valuable, but sometimes the sheer number of options makes it difficult to choose the right one, whether for your specific genre or simply for general learning. Among the many insightful books, On Photography by Susan Sontag stands out. I know this is one of the most frequently mentioned books, and anyone discussing photography theory is likely to bring it up because of how well-known it is. But for me, this book wasn’t just another recommendation; it was one of the first I picked up when I began teaching myself what photography truly was. It shaped my understanding of photography as a form of power.

Susan Sontag alone on a bed. N.Y.C. 1965.

Photograph by Diane Arbus (American, 1923–1971).

Image Courtesy https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/08/magazine/susan-sontag.html

Sontag raises questions that I still consider in today’s digital landscape. When a photographer captures sensitive subjects like injustice or poverty, does it raise awareness, or is it an act of exploitation? Has aestheticizing tragedy become normal or even ethical? Her presentation of both perspectives, evoking empathy and apathy, has changed how I approach image-making.

However, this wasn’t the only issue she tackled. She explored the often-blurred line between photography and reality, how photography itself can be a form of appropriation, and how constant exposure to images can desensitize us to what we see. These ideas continue to be relevant, forcing us to question the images we consume and create, and reminding us that photography is not just about what is in the frame but how it shapes how we see the world.

Take this: a 2016 study from the Journal of Research in Reading discovered that avid readers gain boosts in critical thinking and observational skills. For documentary photographers, these aren't just bonuses; they're vital. The craft is about spotting moments that may pass in a second but tell stories that linger, and reading trains the eye to spot those fleeting emotions, those raw, unrehearsed gestures that speak louder than words. Similarly, a 2017 study from the Creativity Research Journal shows reading nurtures divergent thinking, unlocking fresh perspectives and sparking new approaches. A photographic eye sees more clearly when its mind is well-read.

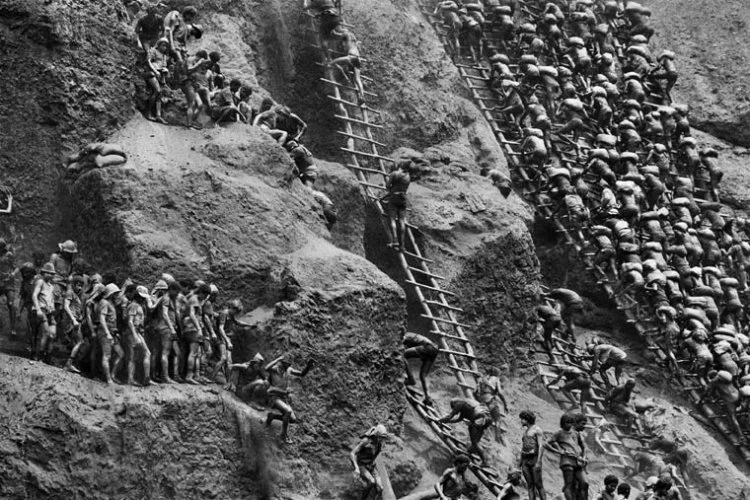

Sebastião Salgado and Dorothea Lange are two documentary photographers whose work was profoundly shaped by literature and social theory. With a background in economics, Salgado drew inspiration from political philosophy, labour history, and environmental writings to contextualize global crises such as migration, famine, and industrial decline. His deep engagement with Marxist theory and humanist literature enabled him to situate his subjects within broader socio-economic narratives, rather than depicting them as isolated instances of suffering.

Three Coal Miners from India

Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age, 1993.

Photograph and book by Sebastião Salgado (Brazilian, b. 1944). Silver gelatin photograph.

Image Courtesy https://www.holdenluntz.com/magazine/new-arrival/sebastiao-salgados-workers-an-archeology-of-the-industrial-age/

Gold miners in Brazil, taken in 1986

Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age

Photograph and book by Sebastião Salgado

Image Courtesy https://redtreetimes.com/2018/04/26/archaeology-of-the-industrial-age/

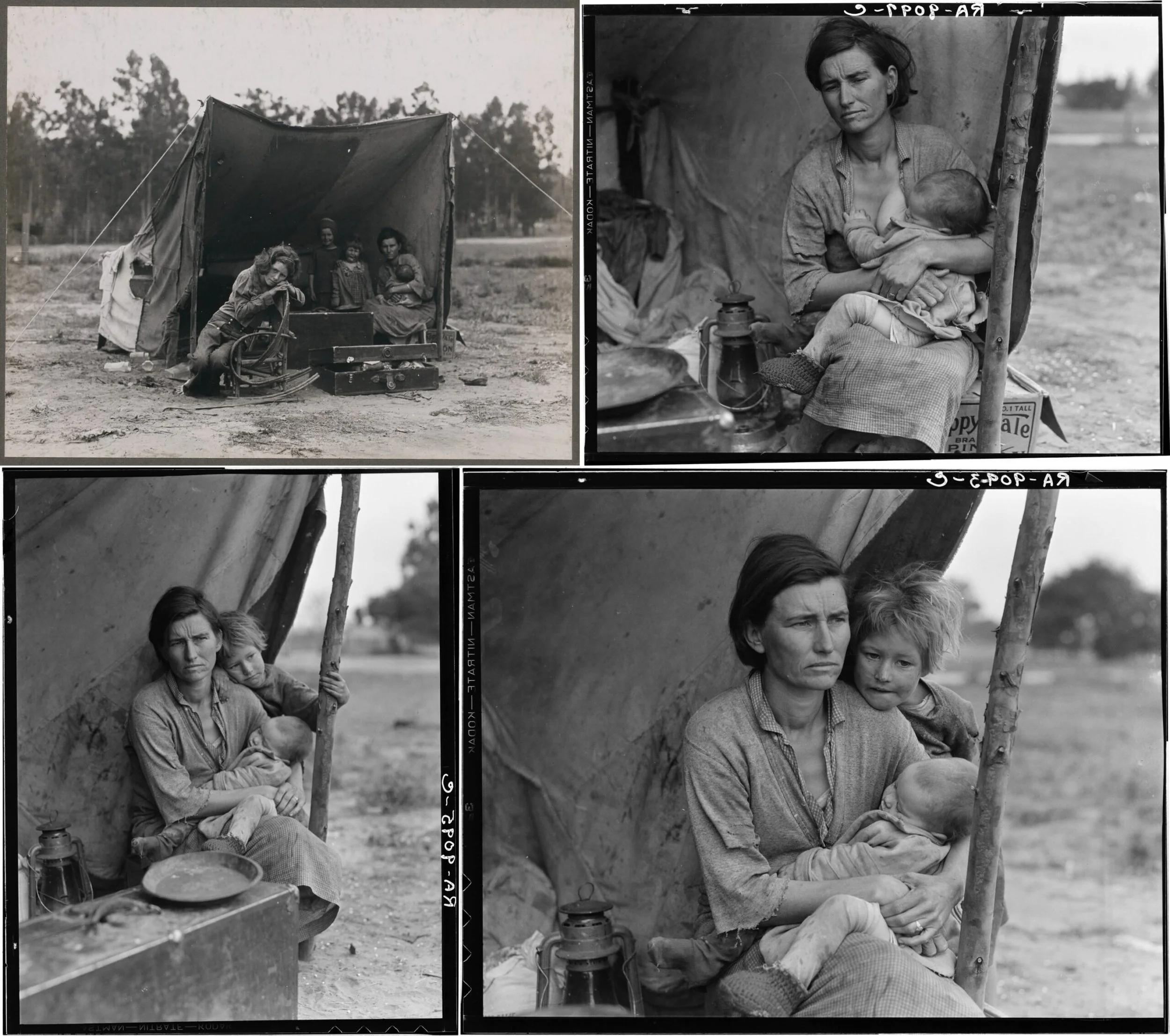

Similarly, Lange’s photography was influenced by social reform journalism, government reports on poverty, and novels like *The Grapes of Wrath*, which resonated with the realities she documented during the Great Depression. Her understanding of economic policies and firsthand accounts of displaced families enabled her to capture hardship with both emotional depth and historical accuracy. For both photographers, reading was not just an addition to their craft; it was essential in shaping their perspectives and ensuring that their images conveyed visually compelling and intellectually grounded stories.

Migrant Mother, 1936.

Photograph by Dorothea Lange (American, 1895–1965).

Image courtesy https://smarthistory.org/dorothea-lange-migrant-mother/

Roland Barthes' Camera Lucida hits closer to the heart, examining every captured image's personal and universal forces. These aren't "how-to" manuals but springboards for deeper thinking about what we choose to capture and, more importantly, why.

So, what does all this mean for a photographer's work? It means that reading paradoxically pulls us closer to life. It broadens how we see, nudges us to notice more, and enriches our work. Photography becomes more than snapping a shot; it becomes a layered, thoughtful, and resonant interpretation of the world. In the end, reading shapes documentary photography in ways that go beyond the technical. It's not just about "taking pictures"; it's about seeing the world more deeply and letting that insight guide each image's story.